Background

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) has been a key health system target since the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Moving towards UHC requires countries to reform their health systems to guarantee population access to good quality healthcare services while protecting users from financial hardships. While there is a no-one-size-fits-all path to achieving UHC, increasingly, countries are prioritising purchasing reforms.

Purchasing of health services occurs in either of two forms 1) passive purchasing – where the purchaser buys services based on the available budget or bills presented, and 2) strategic purchasing – where the purchaser continuously and deliberately uses information to determine the set of services to be purchased, list of providers to engage (provider identification and contracting) and modalities to paying them. Provider contracting is a critical aspect of strategic purchasing. Most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have mixed health systems comprising public, private-for-profit and private non-for-profit (faith-based and other non-governmental organizations) providers (1). For instance, in Africa, the private sector accounts for a significant portion of healthcare services delivered and in most countries such as Kenya, the private sector owns and runs over 50% of the available health facilities (2). Therefore, for governments to engage with private providers, contracts have to be put in place.

Provider contracting is the process of making agreementson the provision of healthcare services, and payment for the services, usually, formalized in written contracts between the purchaser and the provider. Some countries (such as Kenya, Ghana, and Uganda) in the African region have made strides to contract private providers (3,4), while some countries are seeking to embark on contracting private providers. This creates an opportunity for learning and sharing practical lessons from LMICs that have implemented private provider contracting to a relatively successful degree. This blog shares lessons learnt from private provider contracting in Kenya and Ghana, particularly highlighting the requirements for contracting and what has worked or failed to work.

Country purchaser contexts

The National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) is the main public purchaser in Kenya that was established in 1966 and covers 24% of the population as of 2022 (5). Contribution to the NHIF is based on a mix of voluntary contributions of KES 500 (USD 5) for those in the informal sector and mandatory payroll deductions based on a graduated scale ranging from KES 150 (USD 1.5) to KES 1700 (USD 17), and budget allocations from general revenues for state-sponsored schemes (free maternity, indigents etc) (6). The NHIF designs beneficiary service entitlements and engages in the contracting of both public and private providers.

In Ghana, the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) is the main public purchaser of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) established in 2003 and covers 69% of the population (7). Funding for the NHIS is largely from tax sources including a 2.5% earmarked portion of the value-added tax levy on goods and services, 2.5% of Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) contributions per month, return on National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) investments, premium paid by informal sector subscribers (8). Similarly, the NHIA designs beneficiary service entitlements and engages in the contracting of both public and private providers.

Lesson 1: Legal and regulatory frameworks should be in place to support private provider contracting

Private provider contracting should be enshrined in law. In both countries, it was clear that prior to their public purchasers engaging with private providers, there were explicit laws that provided the mandate for private provider contracting. For instance, in Kenya, the operationalisation of the contracting of private providers by the NHIF is established under the 1998 NHIF Act (amended in 2022) which stipulates the process of provider contracting from provider empanelment (Section 30) to provider payment (Section 22).

Similarly, private provider contracting in Ghana is enshrined in law as stipulated in the National Health Insurance Act of 2012 (Act 852) under section 32 on credentialing of healthcare providers, section 36 on claims payable to healthcare providers and section 37 on provider payment systems.

Consequently, countries starting on the journey to contract private providers should first establish a legal basis. Having the legal basis for contracting private providers is an essential step as it brings transparency, and legitimacy, and establishes a modus operandi in the process of private provider contracting. Additionally, for successful contracting, a set of regulations and standards for the operation of private health facilities is crucial. This could either be set by a regulatory or accreditation body, or in its absence, by the purchaser. Without this, it is difficult for purchasers to select providers to contract in ways that promote quality of care.

Lesson 2: Private provider contracting is influenced by actor interests

While it is evident that the engagement process between the purchaser and private providers should be enshrined in law, more often than not, the process is influenced by actor interests that might stall, completely prevent or bias the objective process of private provider contracting. For instance, the renewal of contracts by NHIF in Kenya was faced with huge resistance from private providers who declined to sign contracts citing inadequate engagement during the design of the contracts and the proposed payment rates.

Therefore, it is essential to consider the interests of different stakeholders throughout the private provider contracting process with a keen interest in understanding and incorporating their interests, obtaining their buy-in, and establishing a shared understanding for the successful implementation of the private provider contracting process.

Lesson 3: Private provider contracting is not a one-off event but a continuous cycle

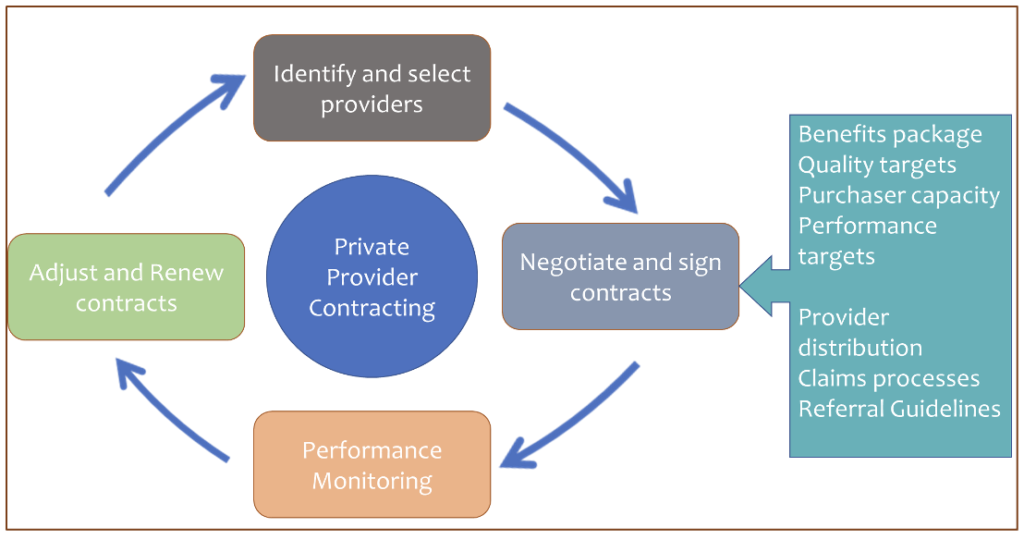

In both countries, the contracting of private providers is not a one-off event but rather a continuous engagement involving a continuous pursuit of the set of healthcare providers to contract through periodic evaluation of the range and quality of services they provide, periodic negotiation of contracts, monitoring of provider performance, and adjusting and renewal of contracts (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Private provider contracting process

Countries planning to contract private providers should assess their ability and capacity to continuously engage in this process. For instance, the purchaser should assess whether they have the resources (funds and human resources) to monitor provider performance, reimburse private providers, and absorb additional administrative burdens whilst addressing sustainability concerns. Provider monitoring capacity, the capacity of a purchaser to monitor the performance of a contracted private provider (monitoring for quality, maintaining standards, and checking that claims are legitimate), was seen to be particularly key to successful contracting.

Conclusion

Private provider contracting has extensive benefits in improving access to quality healthcare services for a population. Countries that seek to design and implement private provider contracting can find valuable lessons from countries such as Kenya and Ghana that currently contract private providers. First, countries starting the process of private provider contracting should establish the legal basis for contracting private providers. Additionally, availing a set of regulations and standards for the operation of private health facilities through a regulatory or accreditation body, or in its absence, by the purchaser is a crucial step. Second, countries should ensure adequate engagement of all stakeholders (citizens, private providers, civil society groups etc.) during the design, implementation and review of the contracting process. A focus on this should be given to the use of evidence and transparent procedures in order to build trust and buy-in among stakeholders. Third, beyond consideration of actor interests, purchasers should assess their own capacity to; set regulations and standards, absorb the additional administrative burden of contracting private providers, reimburse private providers considering their profit-maximising incentive and execute provider monitoring for quality, maintaining standards, and ensuring that claims are legitimate.

REFERENCES

1. Strategic Purchasing for Universal Health Coverage: A critical assessment the public integrated health system in enugu state, nigeria. 2016.

2. Moturi AK. Suiyanka L. Mumo E. Snow RW. Okiro EA, Macharia PM. Geographic accessibility to public and private health facilities in Kenya in 2021.

3. Suchman L. Accrediting private providers with National Health Insurance to better serve low-income populations in Kenya and Ghana: A qualitative study 14 Economics 1402 Applied Economics 16 Studies in Human Society 1605 Policy and Administration. Int J Equity Health. 2018 Dec 5;17(1).

4. Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Ssennyonjo A, Cashin C, Gatome-Munyua A, Olalere N, Ssempala R, et al. Strategic Purchasing Arrangements in Uganda and Their Implications for Universal Health Coverage. Health Syst Reform. 2022;8(2).

5. KNBS. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2022 Key Indicators Report 2023. Available from: www.DHSprogram.com (accessed on 20.07.23 at 1pm).

6. Mbau R, Kabia E, Honda A, Hanson K and Barasa E. Examining purchasing reforms towards universal health coverage by the National Hospital Insurance Fund in Kenya. International Journal for Equity in Health (2020) 19(1)

7. Ghana 2021 Population and Housin Sensus vol 3.

8. NHIS website. https://www.nhis.gov.gh (accessed on 20.07.23 at 1.03pm)

AUTHORS

Jacob Kazungu is a PhD Fellow in the health economics research unit at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Nairobi programme. His research interests include health financing, health policy, patient preferences, equity, efficiency and economic evaluation of healthcare interventions. He also has a keen interest in choice modelling and stated preference survey design.

Dr Lizah Nyawira is a dynamic Health Economist with over 8 years of health systems development and improvement experience. She is adept at leading health financing efforts, health technologies assessment, program planning, research and monitoring and evaluation of health programs and is currently leading the evidence generation and learning pillar at SPARC.