Agnes Munyua, Nkechi Olalere, Cheryl Cashin

On May 19th, the Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Center (SPARC) hosted a webinar in the series “Strategic Health Purchasing Progress: Changing the Conversation.” This title raises the question — changing the conversation from what to what? Conversations about strategic health purchasing often center around questions like “what works?”; “does performance-based financing work?”; “did that pilot work?” We think a more useful question is “What drives progress?” What can countries do to build strategic health purchasing functions and systems that get large-scale, sustainable results? That brings us to the topic of the first webinar in the series: Strategic Health Purchasing Progress — a Theory of Change and Practical Steps.

“Strategic purchasing” means that public purchasers (e.g. Ministry of Health, health insurance agency) exert their purchasing power to make decisions about how to allocate pooled funds to health care providers — those decisions include which services to buy, from which providers, and how to pay — deliberately based on priorities, objectives the system aims to achieve, and information.

A Theory of Change

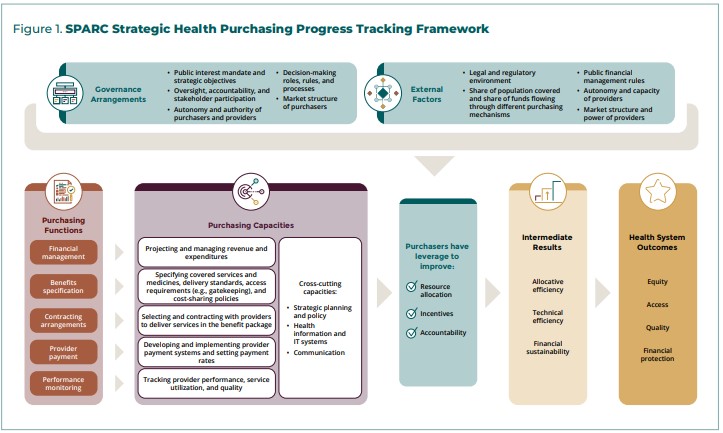

To begin to answer the question about what drives progress, SPARC and its 11 technical partners from across Africa developed a theory of change. This theory of change proposes that a strong strategic purchasing system carries out a set of core functions — benefits specification, contracting arrangements, provider payment, and performance monitoring. These functions are supported by clear institutional arrangements that allocate the responsibility for carrying out the functions, and governance structures to provide oversight, accountability and reporting lines, and to ensure effective stakeholder participation (Figure 1). The theory of change also acknowledges that strategic purchasing is not only a technical exercise but can also be highly political, so policy advocacy, awareness, and practical evidence can be helpful to get strategic purchasing on the policy agenda and to navigate the politics.

When these elements of a purchasing system are in place, the purchaser has “purchasing power;” that is, the purchaser can directly influence the allocation of resources (prioritizing services and population groups, geographies, types of providers, etc.), create incentives that drive individual provider behavior toward objectives, and strengthen accountability through contract enforcement and performance monitoring. These levers can in turn exert influence on intermediate results to improve efficiency and sustainability of the health system, and ultimately equitable access to good quality health services without financial barriers.

However, purchasing power can be enhanced or mitigated by factors outside of the control of the purchaser. Some of these factors include the share of funds under the control of the purchaser, the negotiating power of (especially private) providers, and the financial and managerial autonomy of (public) providers.

Strategic Purchasing Functional Mapping

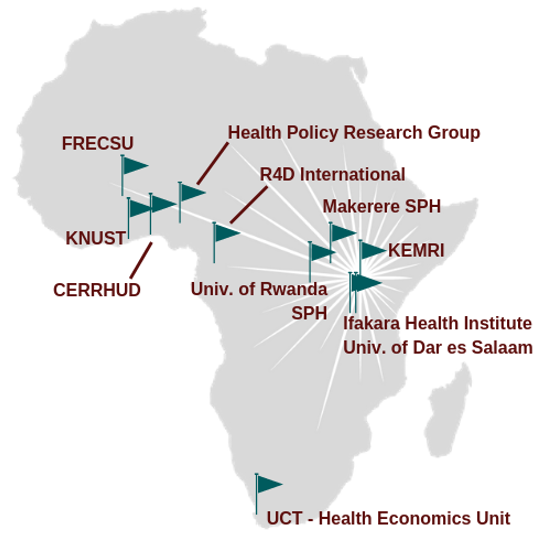

SPARC’s technical partners used this theory of change to assess health purchasing across all health financing arrangements in 9 countries — Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda — and together generated some lessons about what drives, and what inhibits, progress in strategic purchasing.

SPARC’s technical partners

The functional approach to describing strategic purchasing across all health financing arrangements in a country took the focus off individual schemes and facilitated more practical discussions between technical experts and policymakers to identify priority areas to strengthen strategic purchasing.

What were some of the early lessons that came out of the strategic purchasing functional mapping in 9 African countries? All countries have made progress on most purchasing functions in at least some health purchasing arrangements or schemes. All countries have specified benefits packages that prioritize services to address the health needs of the most vulnerable groups. And they have introduced contracting, often with both public and private providers, to clarify expectations and priorities. Less progress has been made on the functions of provider payment and performance monitoring, although all countries are making advancements in these areas.

This progress has not led to large-scale health system improvements in most cases, however, because of the persistence of out-of-pocket payments as the dominant source of health funding, and the high degree of fragmentation, with multiple schemes and purchasers duplicating coverage of some population with multiple service packages and multiple payment methods, often with conflicting incentives. Because fragmentation stems from multiple uncoordinated revenue sources and schemes—some driven by political interests or donor priorities–we consider this to be largely a political challenge.

The countries also faced technical challenges with purchasing policy—such as introducing effective provider payment systems and using performance monitoring to inform purchasing decisions — and operational challenges paying health care providers on time and reducing the administrative burden of purchasing arrangements for both purchasers and providers.

Policy briefs on the strategic purchasing functional mapping in all nine countries can be found here as they become available.

Practical Steps to Make Progress on Strategic Health Purchasing

The three panelists who presented during the SPARC webinar—Dr. Lydia Dsane-Selby (CEO of Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme — NHIS), Dr. Regis Hitimana (Deputy Director General in Charge of Benefits of Rwanda’s Social Security Board — RSSB), and Mr. Raymond Kiwesa (Coordinator of Direct Health Facility Financing for President’s Office of Regional Administration and Local Government — PORALG in Tanzania) offered some practical steps to overcome the political, technical and operational challenges standing in the way of progress on strategic health purchasing.

Reducing fragmentation in purchasing arrangements

Both Ghana and Rwanda have been able to consolidate their purchasing systems over time by integrating community-based health insurance systems (CBHI) into national systems. These major reforms required a combination of political will, technical steps, and trust. But all of the panelists agreed that countries do not have to wait until major consolidation of health financing arrangements becomes politically feasible to take steps to de-fragment purchasing arrangements. In Rwanda, consolidation is also taking place at the level of the purchasing function by consolidating the accreditation function to be used for purchasing decisions in both the CBHI and performance-based financing (PBF) schemes. In Tanzania, different funding streams, including donor funds, are consolidated at the level of the health care provider through direct health facility financing.

Improving health purchasing functions

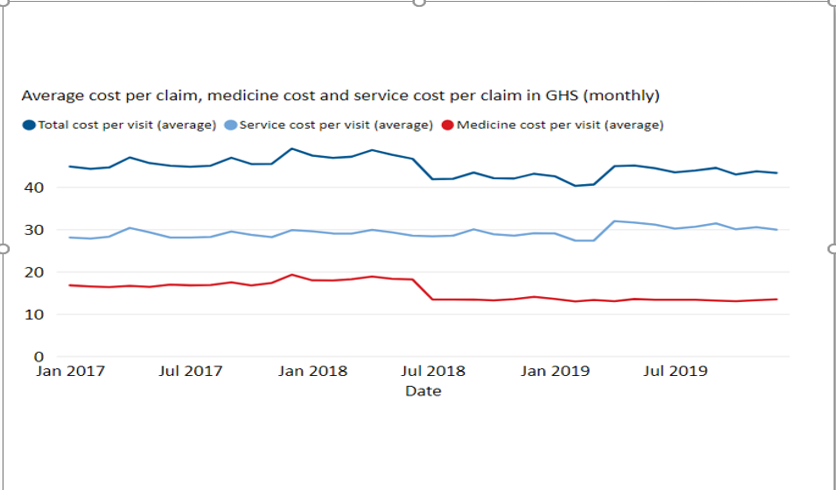

All of the countries showed how powerful purchasing functions can be when fragmentation is reduced and purchasing power is increased. Ghana has been able to use the purchasing power of the NHIS to move toward framework contracting for medicines that allow stronger price negotiation, which is important progress given the financial drain that inefficient medicines expenditure often place on limited health resources. Reducing medicines cost has stabilized the cost per claim in the NHIS, which is important movement in the direction of financial sustainability.

Improving operational systems

Health purchasing has been supported by improving digital and mobile technology in Ghana, Rwanda and Tanzania, which is reducing administrative burden for providers and obstacles to access to coverage and services for beneficiaries. In Ghana, NHIS membership renewal and service authentication are now less burdensome through mobile technology, so the NHIS can more efficiently expand coverage and verify services for payment. In Rwanda, beneficiary enrollment in CBHI has increased through an automated central registration system. In Tanzania, the introduction of direct health facility financing has gone hand in hand with improved provider monitoring, through the Facility Financial Accounting and Reporting System (FFARS).

Where to go next?

While fragmentation and the persistence of high out-of-pocket payments for health continue to limit the power of strategic purchasing in sub-Saharan Africa, progress is possible. The webinar panelists provided some suggestions for where countries can focus their efforts.

- Better data — all purchasing functions rely on high-quality, timely data. Data systems can be improved and de-fragmented, even while larger scale consolidation of health financing arrangements may be a long way off.

- More inclusive communication — all stakeholders (purchasers, health care providers, communities) need to understand how strategic purchasing can benefit them so they can be part of the shared responsibility for making best use of limited resources for UHC

- More flexibility — strategic health purchasing requires systems and structures that are responsive to new funding flows, new incentives, and new accountability systems.

Let’s keep this conversation going! Please join us on the SPARC resource hub and on social media (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) to continue to share experience and lessons on what drives progress on strategic health purchasing.

#ChangingtheConversation

About the Authors

Agnes Munyua, MA, is a senior program officer, specializing in health financing, at Results for Development (R4D) — which launched SPARC in partnership with Amref Health Africa, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. R4D continues to serve as a technical partner to SPARC.

Nkechi Olalere, M.D. is the executive director of SPARC, with 20 years of health financing experience as well as expertise in cross-functional areas of health in sub-Saharan Africa.

Cheryl Cashin, Ph.D., is a health economist and managing director of R4D’s global health practice.